Del Norte man launched early effort to clean up movie industry

DEL NORTE—Unfortunately for many, apparently, the immediately popular movement against sexual misconduct did not begin with the “me too” movement, a cover on Time magazine or, most recently, at the Golden Globes awards program.

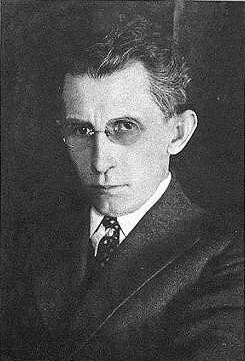

In fact, it began well over 100 years ago when Del Norte, Colo. born, Denver educated ‘Scottie’ Dawley decided that something needed to be done to preserve the then nascent film industry from its own self-established excesses.

Even then, in 1917, Hollywood had been described as a “sewer of depravity” and sooner or later that same excess came to be recognized in the political, entertainment and journalistic industries. But it didn’t even begin there; it was first noticed in the last century and attention was paid by some at that time.

According to one of the leading participants, J. Searle Dawley, in the spring of 1915 eight or nine “met secretly one night in a mountain resort” to consider how to remedy a situation which was gravely damaging to their livelihoods.

To benefit themselves and to promote their interests in an industry dominated by producers and to do something about the “decadence” which was then rampant in world of motion pictures, they proposed to form a formal association.

“Envy and malice” had engendered a “wave of slander” directed against the movie industry that threatened its viability.

Dawley was appointed the “scenarist” of the group. His job was that of a secretary of the organization that arose from their indignation, the Motion Picture Directors Association.

The organization was incorporated that June as a not-for-profit organization to “maintain the honor and dignity of the profession of motion picture directors.” This entity promoted the profession in an era when cameramen were still considered mechanics who, for the most part, controlled the filmmaking processes.

Later leadership also tackled matters such as censorship, runaway production and the producers’ promotion of technology over meaningful content.

Public outcry over the objectionable content in movies resulted in their fight against legislative menaces of censorship and so-called Blue Laws, noting also that the influence of the directors was more potent than that of the schoolteacher, urging them to uphold what they referred to as “certain standards of cleanliness and decency.’

By 1939, Dawley wrote, “the MPDA is dead as a doornail,” blaming the producers for killing off the organization.

A new generation of directors, 12 in number, met in 1935 to form the Screen Directors Guild which shared the sentiment of J. Searle Dawley, the self-described “first professional movie director,” according to Jon Hopwood’s history of that organization.

In his history of the organization, Steve Pond credits the group with setting out “to curb the producers’ casting couch.” A key aim, wrote Dawley, was “to try helping each other and to endeavor to clean up the [motion picture] business from the habit of exporting girls who are weak on the side of resisting flattering offers by certain executives of the business. Directors were often forced to use girls in their art whose only qualifications was that of being a friend of so-and-so or the producer’s girlfriend.”

The moral outrage went further than that. Another founding member, Charles Giblyn, described the initial meeting as “indignant” and said the general public thought of the studios as “habitats of criminals and vagrants.”

The Internet Movie Data Base [IMDB] says one of Dawley’s lasting legacies was his role in forming an organization for directors that eventually would morph into the Directors Guild of America.

According to his papers housed at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Dawley was among the first to address decadence and improving the image of the industry.